A couple of weeks ago, I published a podcast (Episode 141) about the Xposure festival in Sharjah, UAE. Since then, I have had time to further reflect on this event, and the more I have thought about it, the more profound and important it has become. I therefore wanted to put my thoughts down on the written page in addition to the podcast.

If you’re a photographer, especially one who’s burned out on the usual camera trade shows that (let’s be honest) feel more like gadget fairs than creative gatherings, then Xposure 2026 in Sharjah was something that not only hit differently but was not to be missed. This wasn’t another event where you walk miles to see the latest lens dumps and sensor wars. Instead, it was a place built around photographs, photographers, and actual visual storytelling. Imagine that? A festival about photography that actually focused on the creative output of photographers. And honestly, as someone who’s been doing this for a few decades and witnessed more than my fair share of photography festivals and trade shows around the world, what happened in Sharjah this year was profound. It felt like the future of what our community could be and where I genuinely think we should be headed as a global creative collective.

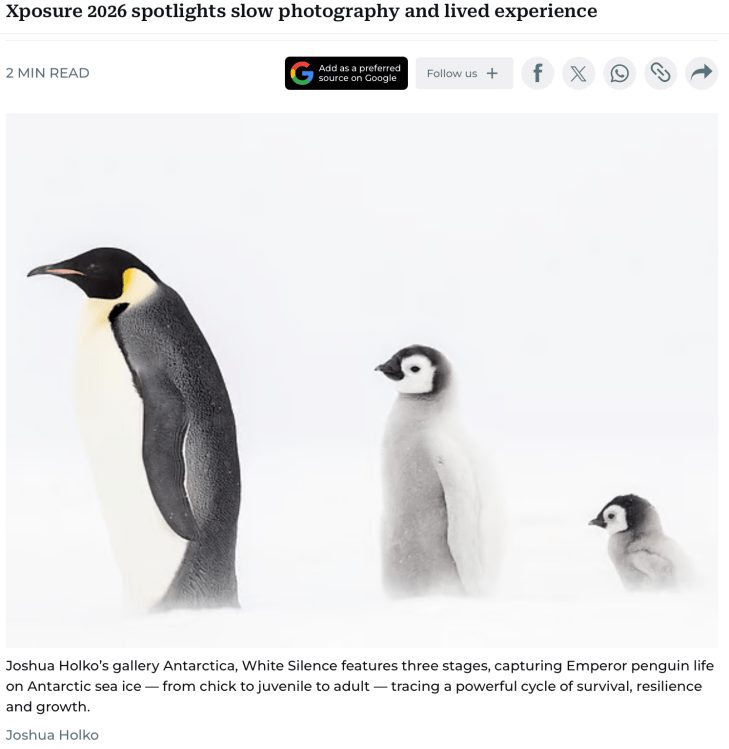

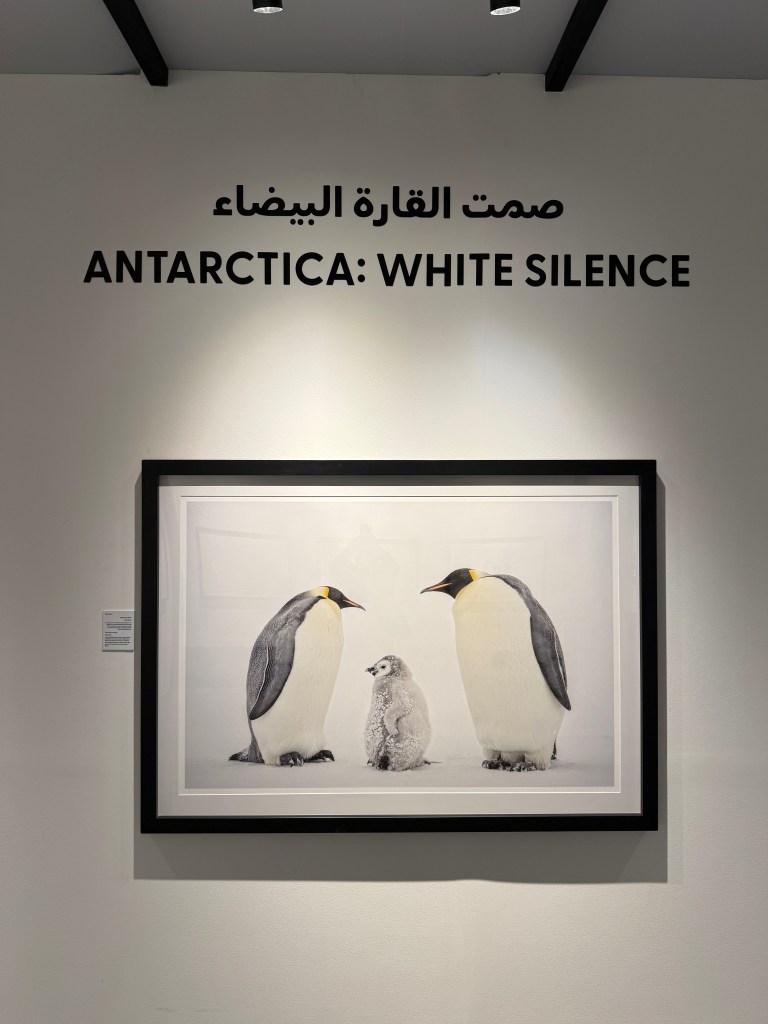

Sharjah’s Xposure 2026 didn’t just celebrate photography. The festival celebrated images that had meaning and power. Under the theme “A Decade of Visual Storytelling,” this 10th edition was huge, featuring more than 95 exhibitions (including my own from Antarctica), over 3,200 artworks, and 570 events, including talks, discussions, workshops, and portfolio reviews, spread across 12 thematic zones. Photography wasn’t reduced to specs and sales pitches; it was humanity distilled through frame after frame. And that’s what made it not just huge in scale but meaningful in spirit and incredibly refreshing.

Walking into the venue at Aljada, Sharjah, was like crossing a threshold into another world. A world where each room was a story waiting to be felt, not just looked at. It was electric with curiosity, challenge, emotion, and craft, and it had a pulse that I have never experienced at any other photography show. Instead of a hundred booths screaming about new gadgets and products, I saw walls filled with images that made you stop mid-step, galleries full of documentary work that confronted you with powerful human emotion, wildlife photography that whispered climate urgency, and fine art prints that felt like meditation. By the end of the week, my feet hurt, my heart was full, and my brain was buzzing.

Let me tell you in one sentence what made Xposure remarkable: It wasn’t about the equipment – it was about the people who make the pictures and the pictures themselves. That’s a rare and profound thing, and in 2026, it felt like a breath of fresh air and something worth celebrating.

Walking from gallery to gallery, you encountered human stories that punched you in the gut or lifted you up with beauty. And this wasn’t surface-level imagery. This was deep engagement with subject, place, and idea. I was truly stunned by the breadth and depth of work on display. From documentary masters to emerging voices, from experimental fine art to environmental narratives. Every exhibition carried weight and purpose, and that is what the best photography does.

There were world-renowned photographers I’ve admired for years and new voices whose work stood shoulder to shoulder with legacy names. The documentary images of war’s aftermath hit me hard. Galleries where identity, suffering, and human complexity were captured with thoughtfulness, power and nuance. Street photography that wasn’t just about visuals but social observation. And every step deeper into the festival revealed layers I didn’t expect, and that surprised me. From travel, adventure and underwater imagery that actually made you want to step into another world, to documentary photography that carried real historical weight. By now, I hope you get the picture that this was a festival of imagery, not a sales pitch for gear.

My own exhibition, Antarctica, White Silence, was part of this conversation. Showing stages of emperor penguin life through a multi-year body of work that has been a lifelong passion project. What surprised me so pleasantly at this festival was standing next to images that told stories about oceans, climate, identity, and humanity with equal force. I genuinely walked away from this festival feeling like photography as a medium is alive, thriving, and evolving. This was photography not just as documentation, but as art, as social language, and as a catalyst for empathy.

And just to be clear, gear was there. There were a number of brand pavilions and technology showcases (including Canon and Nikon). But they sat quietly in the background, because the heart of the festival was squarely on photographers. The emphasis was crystal clear. The gear supports the craft. It doesn’t define it. That alone felt revolutionary compared to most shows where big shiny booths and marketing hype take centre stage.

This wasn’t just a festival for Sharjah, Dubai or the UAE — it was global. Over 420 photographers and artists, from what I believe were more than 60 countries, came together. That kind of scale, combined with intimate engagement, is rare. You could meet someone from halfway around the world, share insights, and feel like you were part of a bigger conversation about the role of photography in the world today.

During the festival, I was also fortunate to be invited for a 45-minute private interview at the presidential palace about my exhibition. This was an incredible experience and an absolute honour to be invited and to take questions on my work from Antarctica. The interview will be aired later this year in Sharjah and Dubai. Some behind-the-scenes photographs below.

What I discovered is that Xposure isn’t just a photography festival. It is a global cultural platform. By embracing both still photography and film, by dedicating creative space to environmental storytelling, portraiture, travel, fine art, and documentary practice, and by weaving in talks, workshops, and performances, the festival became a kind of living museum of visual narratives. And that is super cool.

So why do I call Xposure 2026 game-changing? Because it felt like a festival that remembered why we pick up cameras in the first place. It focused on photographers and photographs over equipment. It celebrated stories over specs. It invited learning and dialogue over passive consumption. It was inclusive and inspiring in equal measure. It was both a place and a festival where creativity was the true currency.

In an era where so many photography trade shows feel like giant tech expos masquerading as creative gatherings, Xposure reminded all of us that the medium is human before it is technical. That the stories we tell and the moments we capture are what connect us across borders and differences. That photography is a language all its own, and when nurtured properly, it can change how people see the world.

I left Sharjah feeling reinvigorated and hopeful. Not just because of the photos, but because of the spirit I saw everywhere. I walked through room after room, each filled with visual narratives that moved me, challenged me, made me emotional, made me think, made me want to go out and tell more stories. That is something you cannot bottle or fake. That is what Xposure 2026 delivered and why I think the world needs to take notice and have more festivals like this.

If you’re a photographer who’s ever felt disillusioned by expos that feel hollow or disconnected from creative practice, put Xposure on your calendar. In fact, book your tickets now (did I mention its free to attend?). Not because of the gear you might see, but because of the stories you’ll carry home with you. Because this isn’t just a photography festival. It’s a global celebration of why photographs matter.