In February of 2026, I ran an all-new Wild Nature Photo Travel 14-day workshop for birds in the Andes Mountain range of Colombia. This intensive bird photography workshop ran from February 10th until February 24th, 2026 and took us across a vast region of the Colombian Andes. We began in the city of Cali on the 10th and finished in the city of Medellin on the 24th of February. Like my Pallas Cat of Eastern Mongolia Report, this trip report will be a little different to the norm and includes a number of behind-the-scenes photographs from the field. Due to my heavy travel schedule, I will come back later in the year and update this post with additional still photographs from the trip as time permits.

Colombia is renowned as one of the best countries on earth for birds, boasting more than 1,950 species, which accounts for almost 20% of the world’s total. This remarkable diversity is due to its tropical climate and varied elevation changes thanks to the Andes and its location between the Pacific and Caribbean coasts. Devout birders have long sought out Colombia as a hot birding destination, but it is only in recent years that photographers have started to seriously get in on the action. This was our first workshop in Colombia, but as you will read below, it most definitely will not be our last.

The KM 18 and San Antonio Cloud Forest areas offer an excellent introduction to bird photography in the Colombian Andes and were our first stops. Within an hour of our accommodation, we found some of Colombia’s best bird feeder setups, each with unique perches and various birds. This area of the western Andes boasts well-preserved habitats for those who enjoy photographing in natural environments. At feeder sites, this workshop targeted species such as the endemics Multicoloured Tanager and Colombian Chachalaca, as well as near-endemics like Scrub, Flame-rumped, Golden-naped, Saffron-crowned, and Rufous-throated Tanagers. In terms of hummingbirds, over 20 species frequent the feeders, including Blue-headed Sapphire, Purple-throated Woodstar, Long-tailed Sylph, Black-throated Mango, Green Hermit, Booted Rackettail, and many more. This was intensive bird photography of many incredible species, offering opportunities from wide-angle to super telephoto.

Our workshop then ascended to the central Andean range, visiting the world-renowned Rio Blanco and Tinamu Reserves near Manizales. Here, we had excellent chances for photographing antpittas, tanagers, and hummingbirds at the feeders, along with many other cloud forest and mountain birds.

After further ascending, we focused on species adapted to high elevations in Los Nevados National Park, with the beautiful Nevado del Ruiz as a backdrop. We spent a day at Hacienda EL Bosque, where the stars of the show are Grey-breasted Mountain-Toucan and Crescent-faced Antpitta. We also visited El Color de Mi Reves, one of the newer sites in the area. We then headed to the quaint village of Jardin to experience the Andean Cock-of-the-rock lek, where it is common to have more than ten individuals posing for the cameras. Although it was incredible to see this amazing bird, the photography was difficult in the dark forest.

Our accommodation for this workshop included a range of high-quality resort-style accommodations with either shared or private rooms, depending on participant preference. In general, we avoided large hotels and instead focused on smaller, boutique-style accommodations close to our shooting locations. We had meals either at our accommodation or on location, where breakfast and lunch were often provided.

Over the course of the 14-day workshop, we observed and/or photographed more than 200 species! (Our final total for the trip was a whopping 204!) This was an absolutely fantastic result that exceeded expectations for all participants. With 204 species observed over 14 days, we saw on average 14.57 new species every day or more than one species every waking hour! Prior the trip I had not thought we would crack 150 species so exceeding 200 was a complete surprise. A complete list of species is included below by clicking on the download link.

Many of the locations we visited throughout this workshop were specifically set up for birders and bird photographers with individual local guides who specialised in each location. Feeder stations were set up for Hummingbirds at most of the locations we visited, as well as suitably appointed shooting locations for larger species. We photographed far too many species to list them all in the report one by one, but each presented its own opportunities and challenges. The antpittas, in particular, are a real challenge in the dark jungle forests of Colombia. Other species, such as the hummingbirds, present different opportunities and challenges. I frequently struggled with backgrounds in several locations in the dark forest, but was always able to find an angle that worked for me.

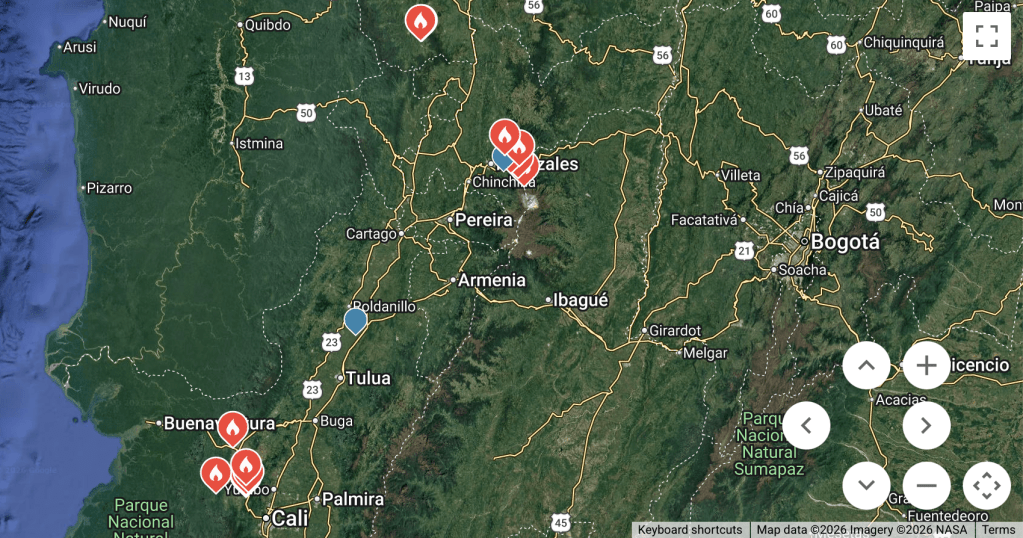

This was an intensive workshop with early starts (often around 5:30am) and full days of photography. We based ourselves in multiple locations in order to give ourselves the best possible opportunities for different species. Over the course of the 14-day workshop, we stayed in four different locations, plus one night at each end of the trip (in Cali and Medellin). The included map below illustrates our main target locations.

In equipment terms, big glass was the order of the trip, and I predominantly shot the RF 600mm f4L IS on the EOS R1; occasionally switching out to the RF 100-300mm f2.8L IS for larger, closer subjects. I did miss my RF 400mm f2.8L IS on several occasions, but the thought of schlepping a third ‘big-white’ through the airports deterred me from packing it. I did use my RF 1.4 TC on several occasions on the 600mm for an effective focal length of 840mm and lamented leaving the RF 2X TC at home for some of the very small, distant birds. I took my Sachtler Carbon tripod and ACE fluid head and used these at every single location to help support the 600mm lens. In hindsight, I would pack the 400mm f2.8L IS in lieu of the 100-300mm f2.8 as I generally have a preference for more (rather than less) telephoto compression.

Other than the small snippet of video above, I shot at 100FPS on the Canon EOS R1; I focused (pardon the pun) entirely on stills for the duration of the workshop. My own personal shot count for the trip was well over 30,000 RAW captures (Canon EOS R1 with pre-capture on High Speed + at 40 FPS!), and culling and editing are going to take quite some time. Many of the participants were well north of my own shot count! Pre-capture proved decisive on this workshop and enabled me to capture images of Hummingbirds that would have otherwise been impossible. Likewise, the auto focus system on the EOS R1 proved up to the task and consistently nailed focus on the fast-moving birds. Just as an aside, I am currently in the market for new CF Express Type B cards V4 – if anyone has a recommendation please let me know.

In terms of additional equipment I did not take with me: I will on the next trip pack both a small silver reflector to throw some additional light on the small hummingbirds in overcast conditions, and a small portable backdrop I can set up for the more difficult forest birds. It is certainly possible to use flash at many locations, but I generally prefer natural light photography. I may pack a small modelling light for the very dark forest birds.

The Andes (which runs the spine of South America) is a significant mountain range by global standards, and during the workshop, we ascended to a maximum altitude of 4125 metres (13,460 feet) in pursuit of the Buffy Helmetcrested Hummingbird (amongst other species). The Buffy Helmetcrested Hummingbird is specialised in high-altitude ecosystems, endemic to Colombia and found only in one very small part of Colombia. These small hummingbirds are characterised by a prominent crest and facial plumes that make them unique and highly sought after by birders (and very photogenic). This was a species I did not personally photograph, but very much enjoyed seeing in the wild as it flitted around the high-altitude flowers and plants.

We also photographed six different species of Antipa, a whopping 41 different Hummingbird species, five species of Woodpecker, Hawks, Kites, and so many more different species over the fourteen days we were in the field. For the full list, please check out the e-bird PDF linked above.

Personally, I most enjoyed the Tanigers, Hummingbirds, Toucans and Wrens. All of which we had multiple opportunities to photograph throughout the trip. The swordbill and Long-Tailed Nymph Hummingbirds proved a favourite amongst all of the group for their incredible bill and tail. In terms of the one that got away, it was for me the aptly-named ‘group’ dubbed ‘Bumblebee Hummingbird’. A tiny Hummingbird about an inch long that had amazing character and reminded me very much of the fat dragon with small wings from the film How to Train Your Dragon. This is a species I will try and capture on the next trip with the 600mm lens and 2x Teleconverter.

Temperatures varied considerably throughout the trip, depending on our location. High in the Andes mountains, temperatures were in the low single digits Celsius on several occasions, necessitating warmer layers and even a hat and gloves on occasion. Whereas lower lying areas saw temperatures in the high 20’s and low 30’s Celsius, where it was light shirts, hats and sunscreen. Although we had some rain on ocassion (as expected in the cloud forest areas) we were never prevented from photographing. In fact, the cloud and mist often added to the experience and photographs. The small raindrops on the Hummingbirds added a wonderful additional element on several occasions. Rain will always draw me out to photograph wildlife. The additional element of water always adds a more evocative and emotive feel to a photograph.

On our last day of travel back to Medellin, we made a wonderful three-hour stop at a small bespoke coffee plantation for a deep dive behind-the-scenes tour on all things coffee. The tour took us from the initial planting and cultivation to the finished product. And of course, an opportunity to pick some berries and an extensive tasting! This was a little added bonus for the group that was thoroughly enjoyed and a wonderful way to wrap up our workshop. On our return to Medellin, we farewelled over dinner before our onward flights the following day.

My sincere thanks to all of the participants who took part in this workshop and who placed their trust and faith in my company, Wild Nature Photo Travel to organise first class logistics and shooting locations. My thanks and heartfelt gratitude also to Jose and John, who provided us with brilliant first-class local guiding and driving throughout our trip – thank you. Jose, in particular, deserves special credit for his seemingly endless knowledge of birds and ability to identify a species even from the vaguest of descriptions. Credit to my partner Susanne Ribberheim for the portrait above.

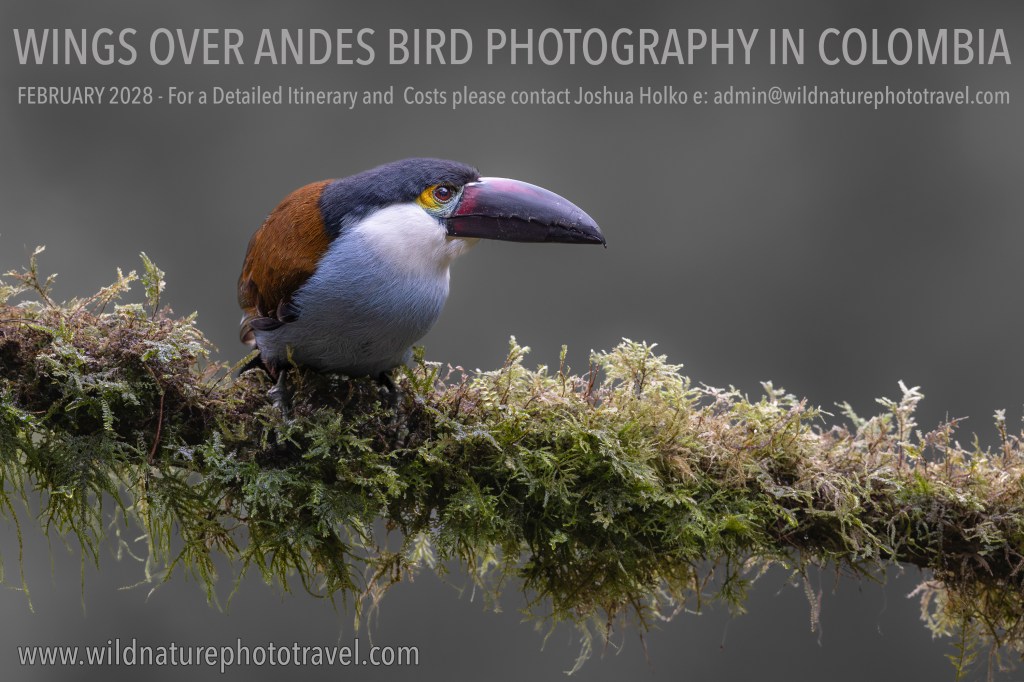

In February of 2028, I will be offering this workshop again for a small group of just six photographers. This workshop is for passionate and keen photographers who want to undertake a deep immersion in bird photography at one of the best places on earth, with the highest number of species. Full details are on my website at www.jholko.com/workshops. Some places are already spoken for so please do not delay to avoid disappointment.

Travelling on this bird photography workshop to Colombia is about far more than simply adding species to a list. It is about immersing yourself in one of the most biodiverse countries on Earth with purpose, patience, and photographic intent. Colombia is a kaleidoscope of colour and sound, home to an astonishing variety of hummingbirds, tanagers, toucans, antpittas and endemic species found nowhere else. This is a workshop where you will develop your ability to read the light, improve composition, and storytelling. This is about going beyond opportunistic snapshots and moving toward crafting powerful, considered images that truly reflect the vibrancy and intimacy of these birds in their environment. Please contact me for further details.