Puffins, Solitude, and the Soul of the Arctic – There are few places left in the world where you can photograph wildlife in complete solitude—where the only sound is the rush of wind across dramatic basalt cliffs, the echoing cackle of seabirds, and the soft high-speed click of your mirrorless cameras electronic shutter. Grimsey Island, perched on the Arctic Circle just off the north coast of Iceland, is one of those places. It is wild, raw, and unforgiving—but in its ruggedness lies extraordinary beauty and a rare opportunity for intimate encounters with wildlife. Grimsey is the hidden gem of Iceland, packing a photographic punch well above its size and weight.

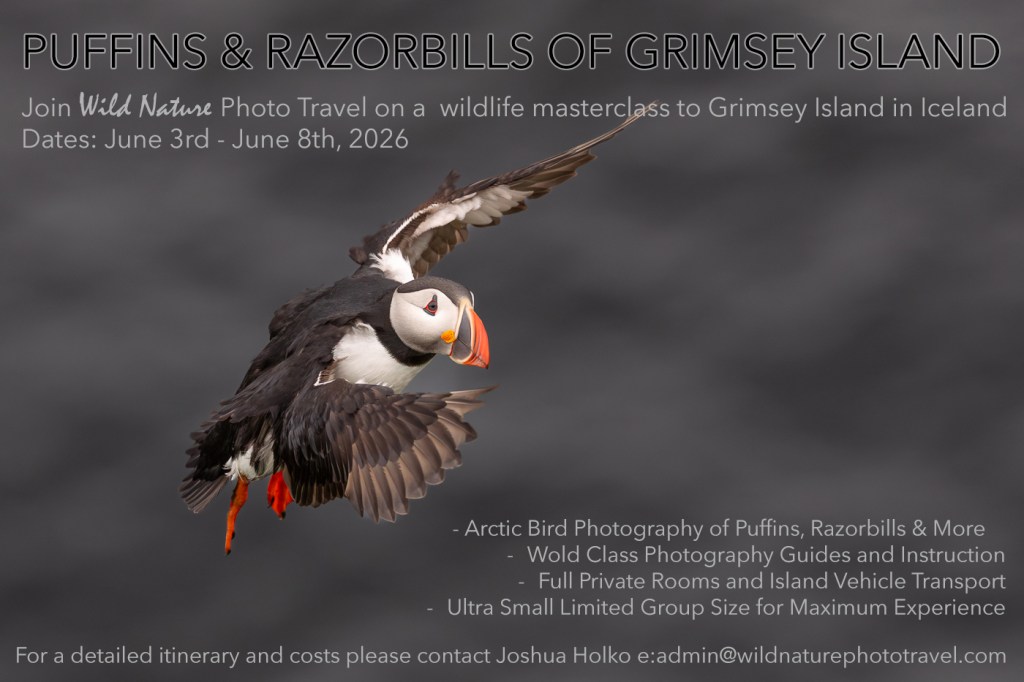

This May and June, I had the great privilege of leading two back-to-back photography expeditions to Grimsey Island focused primarily on the charismatic Atlantic Puffin, but with ample opportunities to photograph a host of other seabirds and Arctic landscapes. The trips—May 27th to June 2nd and June 3rd to June 8th—delivered not only exceptional bird photography but also some of the most dramatic weather and moody light I’ve encountered in recent years.

Grimsey isn’t easy to reach, and that’s a good thing. Its remoteness keeps it pristine and blissfully free from crowds. To get there, we journeyed north to the Icelandic town of Dalvík, where we boarded the ferry for the three-hour crossing. The first group arrived smoothly, with calm seas and mild winds—a gentle welcome to the north. But the second trip was greeted by nature’s fury: high winds exceeding 30 metres per second and ocean swells over five meters delayed our departure by a full day. While the delay wasn’t ideal, it provided an impromptu opportunity to explore some Lightroom processing and discuss the optimal camera settings for the upcoming photography. The one-day delay also served as a reminder that in the Arctic, nature always has the final say.

Once we landed on Grimsey, however, everything fell into place. Our home for the week was a humble guesthouse near the island’s southern cliffs—a perfect base from which to venture out for both early morning and late evening sessions. Grimsey is a relatively small island with only a few basic roads. Nevertheless, a car (4WD) is of significant benefit for moving around quickly and accessing the more remote and higher sea cliffs. At both of these workshops, we took a 4WD with us on the car ferry so we could maximise our photography on the island. Other groups don’t necessarily offer car transport on the island, but this can be a significant error of judgment in inclement weather. Over the course of our trip, we watched several groups uncomfortably trudging uphill through the rain with their camera gear, headed for the high cliffs. Meanwhile, we travelled comfortably to the top by 4WD with all our gear, arriving dry and ready to photograph.

The stars of the show were, of course, the Atlantic Puffins. These endearing seabirds return to Grimsey in the thousands each spring to nest high on the cliffs that ring the island’s perimeter. Unlike other sites in Iceland where the birds are often skittish or the cliffs too distant for intimate photography, Grimsey offers something truly special: proximity. Not only does it provide an incredible opportunity to get close to these fantastic birds, but it also offers the chance to photograph these birds in a stunning Arctic setting.

Each day, we were able to approach puffins within mere meters, lying flat on the soft grass as they hung out on the high cliffs or returned to their burrows. With patience and respect for their space, they allowed us into their world. We photographed them in dramatic light, and during moody, misty afternoons that added emotional depth to the frames.

What makes Grimsey exceptional is not just the access, but the solitude. Unlike well-trodden sites on the mainland, we had entire stretches of cliff to ourselves. No tourists and no other visitors. No other groups. Just us, the birds, and the Arctic wind. It’s a kind of photographic meditation—one that allows you to connect deeply with the landscape and your subject.

While puffins were the headline act, they were far from the only performers. Grimsey is a seabird sanctuary, alive with an astonishing diversity of species. Razorbills nested alongside puffins, their bold monochrome plumage striking against the green moss and black cliffs. Black-legged Kittiwakes shrieked and soared on coastal updrafts, offering opportunities for stunning in-flight images as they banked and hovered in the wind. Mixed amongst them were northern Fulmars and common murres.

We watched and photographed Common Murres and Guillemots packed shoulder-to-shoulder on the narrow cliff ledges, each pair tending to a single egg balanced precariously on bare rock. Northern Fulmars glided effortlessly past our lenses on fixed wings, while Arctic Terns dive-bombed intruders with typical ferocity.

We were fortunate to encounter several rarer species as well, including Black Guillemots, the delicate Red-necked Phalarope in its breeding plumage, and even the elusive Little Auk. Each day brought new sightings—Snipe performing aerial displays, Golden Plovers calling from lichen-covered rocks and buttercup-covered fields, Snow Buntings flitting along the coastal paths.

Throughout the two trips, we documented and photographed an impressive list of 30 species. I did not personally photograph every single species, but very much enjoyed keeping a list of those species we encountered.

- Atlantic Puffin

- Razorbill

- Black-legged Kittiwake

- Common Murre

- Brünnich’s Guillemot

- Black Guillemot

- Northern Fulmar

- Arctic Tern

- Red-necked Phalarope

- Snipe

- Golden Plover

- Snow Bunting

- Redwing Thrush

- Raven

- Common Eider

- Long-tailed Duck

- Black-headed Gull

- Gannet

- Black-tailed Godwit

- Common Ringed Plover

- Ruddy Turnstone

- Eurasian Oystercatcher

- Sanderling

- Common Redshank

- Arctic Skua

- Dunlin

- Mallard

- White Wagtail

- Meadow Pipit

- Canada Goose

Each species presented its own photographic challenges and rewards, from fast flight patterns to elusive behaviour. But the overarching theme was access—Grimsey offers unparalleled proximity to birds in their natural environment, free from the pressure and disruption of human traffic.

The Arctic teaches patience and rewards those who are flexible. Throughout our time on Grimsey, we encountered an extraordinary range of weather conditions: wind, sun, sea fog, and sudden downpours. But far from being an obstacle, the changing weather only enhanced our photography. I have long mandated that dramatic weather makes dramatic photographs, and Grimsey delivered in spades for both our workshops.

One particularly memorable morning, fog and mist rolled in off the ocean, blanketing the cliffs in a pale, blue-grey hue. Visibility dropped, but the mood became magical. Puffins stood like statues in the mist, their colourful beaks luminous against the muted backdrop. That afternoon, the fog burned off to reveal crisp skies and overcast light, and we returned to the same spot to photograph puffins against the ocean.

Another evening brought towering clouds that swept across the island like theatre curtains, letting shafts of light fall onto the sea. With long lenses and careful compositions, we captured seabirds soaring through these natural spotlights—a breathtaking juxtaposition of nature’s grandeur and raw simplicity.

Grimsey isn’t just about birds. The island itself is staggeringly beautiful. A windswept plateau broken by basalt cliffs and rolling meadows, it feels like a place lost in time. We explored beyond the nesting colonies to photograph the broader landscape: coastal rock formations, dramatic sky-scapes, and wild, empty vistas that echo the purity of the far north.

At times, the play between scale and subject became a powerful compositional element. A lone puffin perched on the edge of a massive sea stack. A pair of Black-legged kittiwakes on their nest. A group of murres slicing through shafts of light over a cobalt sea. Grimsey gives photographers room to breathe—to pull back and frame the subject in its environment with honesty and reverence.

Perhaps what made both trips so special was not just the wildlife or the location, but the people. Our small, tight-knit groups quickly bonded over shared meals, gear chats, photo reviews, and the inevitable jokes that come after long days in the field. We worked as a team—scouting, spotting, sharing tips and excitement. When one of us found a nesting site or a particularly photogenic perch, the news spread quickly and everyone benefited. There was no competition, just a shared passion and respect for nature and photography. Evenings were spent reviewing images, charging batteries, and discussing light, behaviour, and composition. More than a few nights ended well after midnight, reluctant to put our cameras down even as fatigue set in.

Personally, I shot over 22,000 images during the two workshops on Grimsey Island (not hard when your R1 camera goes at 40 FPS with birds in flight!). After an initial first pass, I was able to delete around 13,000 images, leaving approximately 9,000 keepers (sharp photographs with interesting compositions that are worth a second look). That is an extraordinary number of photographs to sort, edit, process, and catalogue, and the photographs in this report represent just a very small fraction of those I chose to keep and have processed to date. It will likely be many years before I finish mining photographs from these two workshops. This makes Grimsey Island one of the most productive locations in the Arctic to photograph Arctic birds.

Grimsey Island is not a destination to add to your bucket list. It’s something more profound: a place to slow down, to reconnect with the rhythm of nature, and to immerse yourself in the art of observation. It’s a place where puffins aren’t props for selfies but sentinels of a wild world that still exists if you’re willing to seek it. Both of these trips reminded me why I fell in love with wildlife photography in the first place. It’s not about the number of images or the reach of your lens—it’s about presence. About being there. About watching a puffin return to its burrow against the wind, or witnessing the sudden flash of an Arctic Skua as it harasses a tern mid-flight.

If you’re looking for an experience that combines intimate wildlife encounters, cinematic landscapes, and genuine solitude, Grimsey offers something truly rare. I’ll be back—and I hope to see you there, lying flat on a clifftop, your lens trained on a puffin with the wind in your face and the Arctic sun at your back. Details for our June 2026 trip are now online, and places are limited. Please contact me for details – Until next time, stay wild.