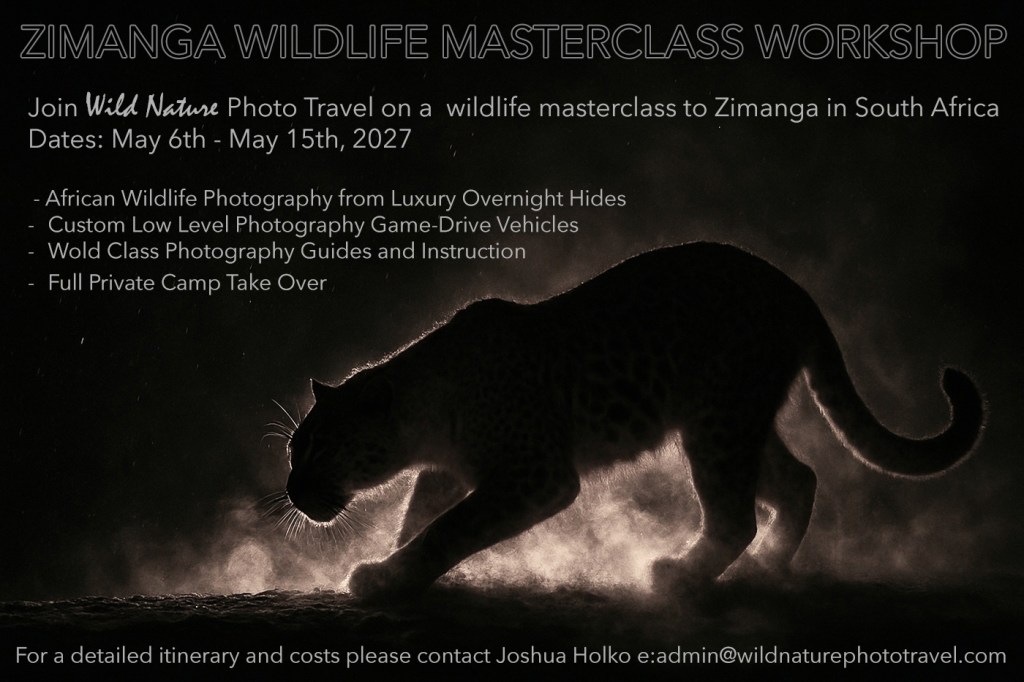

In April 2025, I had the privilege of leading an extraordinary group of photographers on my Zimanga Africa Ground-Level Wildlife Masterclass — a full reserve takeover that provided unparalleled access to one of the most diverse and wildlife-rich regions in South Africa. I’ve long said that Zimanga is one of the most progressive photographic destinations on the continent, and this year’s workshop only reaffirmed that sentiment. With no outside tourists, no sharing with others, unrestricted access to world-class photographic hides, a dedicated team of trackers and guides, and a truly immersive experience in African wildlife photography, 2025’s edition was nothing short of a creative and wildlife-rich success.

There is something profoundly moving about photographing elephants at night. The darkness, punctuated only by subtle, carefully positioned lights, transforms a majestic subject into something even more powerful and ethereal. One of the absolute highlights of this year’s trip — and a resounding favourite among the group — was the overnight experience in the elephant bunker hide. Designed specifically for photographers, this low-angle, comfortable hide allowed us to witness enormous elephant bulls as they came to drink, bathe, and interact under the cover of darkness. Being this close to a fully grown massive Tusker is an awe-inspiring experience not to be missed.

The conditions this year were sublime. With mild evenings and clear skies, although it took some persistence, the waterhole was a consistent magnet for elephants. On one particularly unforgettable night, three bulls approached simultaneously, their massive forms silhouetted against the soft glow of artificial light, mist swirling from their trunks as they drank and sprayed water into the cool night air. The photographic results were staggering — dramatic lighting, perfect reflections, and razor-sharp detail made for world-class imagery. Every single participant came away with portfolio-worthy shots that captured the spirit and strength of these incredible creatures in a truly unique way.

While hides and low-level photo vehicles offer powerful opportunities, few moments compare to the sheer intimacy of walking with a wild predator. Zimanga is one of the only places in Africa where you can photograph free-ranging cheetahs on foot — and this year’s experience elevated that to another level. With the guidance of Zimanga’s experienced trackers and guides, our group approached a pair of cheetah brothers on foot in the open savanna. This pulse-quickening encounter brought a profound sense of connection to the natural world.

Photographically, walking with cheetahs is a dream. We could shoot from low angles, position ourselves with the light, and create immersive, personal, and alive images. The early morning light was golden and soft, with gentle dew clinging to the grass. The cheetahs moved with grace and elegance, pausing occasionally to look directly into our lenses, allowing everyone to create images filled with mood and eye contact. It was, without question, a highlight of the trip and an experience no one will soon forget.

In addition to the hides and on-foot cheetah experience, the photo game drives this year were exceptional. One of the distinct advantages of a full reserve takeover is the exclusivity — we were not restricted by schedules or other tourists. Each photographer had their own row of seats in custom-built vehicles explicitly designed for low-angle wildlife photography. This made a massive difference, allowing everyone the freedom to move, shift, and compose without obstruction. You haven’t photographed in Africa on safari until you have experienced one of these low-angle vehicles.

Weather conditions were ideal — cool mornings with mist clinging to the valley floors, building into warm, dry days with rich, directional light. This meant optimal shooting conditions nearly every session. We photographed everything from rhinos dust bathing at sunrise to giraffes silhouetted at sunset, to close encounters with lions resting in the shade of acacia trees. The ability to work low to the ground from the vehicle provided a completely different perspective, yielding more dramatic and intimate imagery than traditional safari setups allow.

Zimanga isn’t just about the big mammals. The bird photography opportunities this year were phenomenal. The lagoon hide, in particular, was a bird photographer’s paradise. The clean, uncluttered backgrounds and shallow water provided the perfect stage for capturing elegant images of African spoonbills, pied and malachite kingfishers, hamerkops, storks and more.

Our group spent several serene sessions in this hide, working with long lenses to freeze the dramatic dives of kingfishers and the deliberate wading of spoonbills as they hunted. The morning light filtered in just right, casting subtle highlights and rich colours that made for exquisite avian portraits and action shots. The hide design, with glass-fronted opening, allowed for complete immersion without disturbing the wildlife — a critical feature for this kind of delicate work.

The scavenger hide delivered intense action and raw storytelling. Designed with photographers in mind, this hide is positioned over a natural carcass area frequented by vultures, jackals, and other opportunists. Over multiple sessions, we witnessed dramatic interactions as white-backed vultures jostled for position, jackals darted in for scraps, and marabou storks loomed over the chaos like prehistoric sentinels. On one particular morning we also had a visit from a majestic tawny eagle.

For those looking to create compelling behavioural imagery, these scenes were gold. Wings spread wide, dust flying, claws extended — every moment was charged with intensity. The hide’s positioning allowed us to shoot at eye-level, capturing the energy and aggression of these feasts in full cinematic detail. It was a reminder that even the less ‘glamorous’ wildlife encounters can result in some of the most potent images.

A trip of this calibre wouldn’t be complete without comfort and care. The accommodation at Zimanga is nothing short of luxurious — private, spacious rooms with views over the reserve, luxurious bedding, and all the modern amenities you could wish for. After long days in the field, returning to gourmet meals, fine South African wines, and a roaring fire created the perfect atmosphere for review, reflection, and camaraderie.

This level of comfort matters not only for rest and recovery but also for allowing participants to focus entirely on their photography. The Zimanga team handled every logistical detail flawlessly, from meal timing to equipment storage to hide scheduling. The exclusivity of having the entire reserve to ourselves meant no waiting, no distractions, and complete immersion—something that simply can’t be overstated.

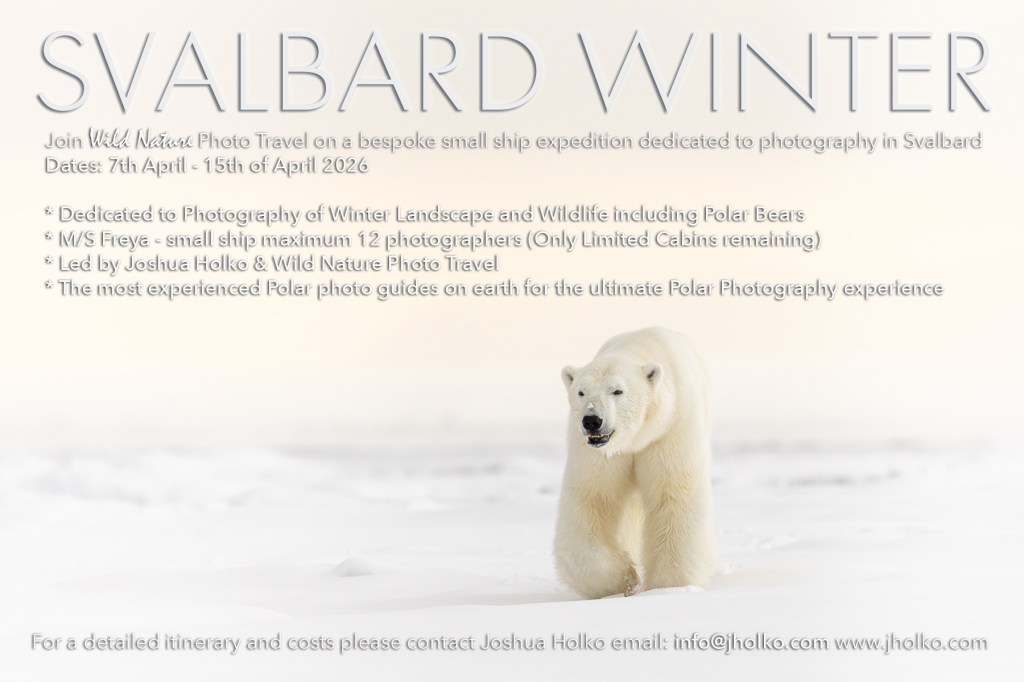

Reflecting on the 2025 Masterclass, I’m already filled with anticipation for our return in 2027. Zimanga remains one of the only game reserves in Africa built from the ground up with photographers in mind, and our complete takeover ensures a bespoke experience designed to maximize photographic potential. This isn’t a workshop where you are forced to share a location with general tourists. This is a deep and private immersion that provides the opportunity to create an emotive portfolio of African images.

In 2027, we will once again take over the entire reserve. That means no sharing with tourists, no rigid safari schedules, and complete access to all hides and photo vehicles. Why is this so important? Simply put, by taking over the entire camp, we can offer multiple overnight and day hide sessions to everyone. This provides many opportunities that would otherwise be missed.

The itinerary will include overnight elephant hide sessions, walking with cheetahs, private photo vehicle access, avian hide time, and exclusive opportunities in the scavenger hide — all under ideal seasonal conditions. We’ll be visiting at the optimal time of year, when weather patterns bring soft light, mild temperatures, and increased wildlife activity. This time of the year, the rains have finished, and this also provides additional opportunities at the watering holes.

If you’re looking to elevate your portfolio, challenge your creativity, and experience Africa in a way few others ever do, Zimanga 2027 is the opportunity. With limited spaces available and the 2025 edition having sold out well in advance, I highly encourage interested photographers to reach out early. Please contact us to secure your place. Full details are available on our website at www.jholko.com/workshops This trip is not just a workshop — it is an immersion into the best Africa has to offer, with a focus on excellence, comfort, and the creation of truly world-class wildlife imagery. See you in 2027.