A few days ago, I received exactly this question via email: ‘What, in your opinion, Josh, is the best workshop for Mammals that doesn’t necessitate a boat? I get tragically sea sick when I even look at the ocean and can’t even entertain the idea of getting on any boat. I know it’s a stupid fear, but I can’t join anything that needs a boat or ship.’ Before we get to my answer, I did seek the author’s permission to write about this, which they kindly agreed to:

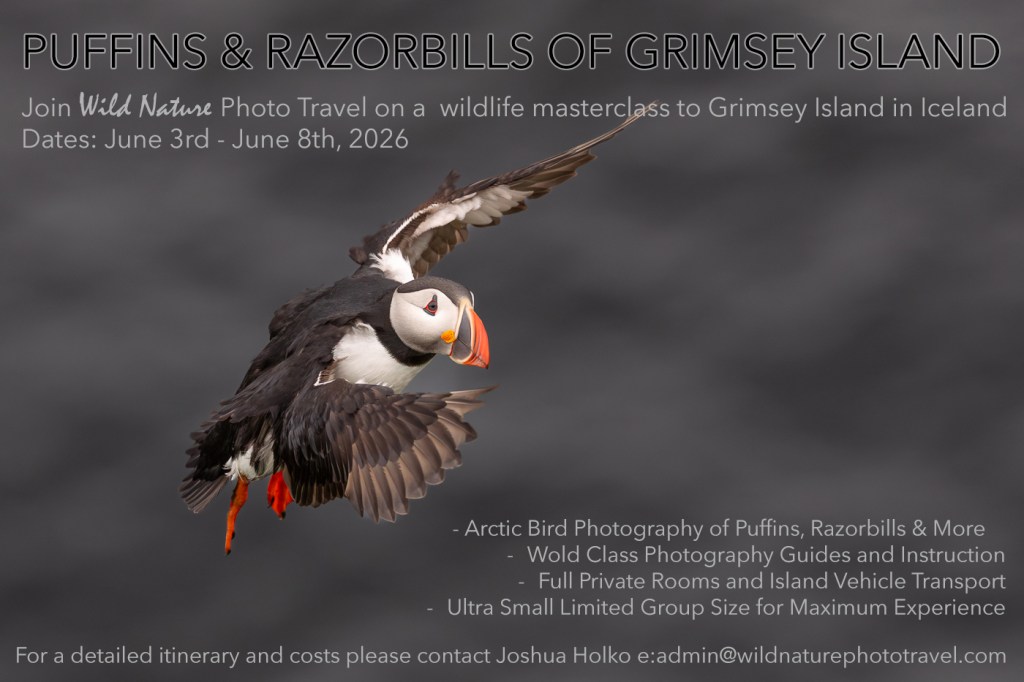

With apologies to the author for my brief chuckle at their thalassophobia, I did not have to stop and think about this for very long. My immediate answer is the Arctic Fox workshop we offer in Iceland in Winter. However, this requires a boat ride (albeit a very short one) and thus takes this workshop out of contention. I realised on a second reading that the question also contained the plural of the word ‘mammal’, and that changes the game further. For others, my answer remains the same, though. If you are happy to target one species specifically and put all your effort and focus (pardon the pun) on that critter, then the Arctic Fox workshop in Hornstrandir Nature Reserve is unmatched for encounters that will leave you breathless and your memory cards full.

However, if you can’t even look at the ocean without getting nauseous and want the opportunity to photograph multiple large carnivore mammals in a stunning Autumn setting, then the Wolves and Bears of Finland are equally unmatched. This is a workshop that will see you depart with memory cards full of keeper images of Wolves and Bears, an ear-to-ear grin and a vastly more profound understanding of wildlife photography. I still hold to this day that Finland (along with Mongolia) is one of the most underrated destinations on earth for wildlife. From the private hides we use, it is common to see and photograph Wild Wolves, Brown Bears and Wolverine – all close up and not at a significant distance. While many hold Yellowstone in the USA as the mecca for Wolves, I can assure you from much first-hand experience that it isn’t a patch on Finland’s offering of these incredible canines.

Northern Finland is the only location I have ever photographed Wolves from, where I came away from a single week-long trip with enough photographs for an entire book – Never Cry Wolf (and yes, I have been to Yellowstone and photographed Wolves there). This is not an isolated incident. Every autumn visit has yielded both incredible opportunities and powerful photographs. In addition to the mammals in Finland, we often photograph both White-tailed and Golden Eagles – all from the exact location. There is also a plethora of smaller forest birds, including such species as the Crested Tit and the Great Spotted Woodpecker. I have even photographed the European Pygmy owl in this region. You can check out the full portfolio for Finland HERE. And, It isn’t just the photography that makes this Finland workshop so special. It is a combination of the ease of access (there is minimal walking required as we drive to the hides – the walk is less than 100m), the homely and cozy log cabin we use as a base and the incredible surroundings of the Boreal forest. Not to mention the breathtaking landscapes around the many lakes in this location. This is a workshop that invites and offers the photographer the opportunity to deep dive into their mammal photography in a location unmatched anywhere on earth, in my experience. Capturing a stunning portfolio is only the beginning. Expect to come away with not only powerful and evocative images, but a deeper appreciation of Nature and a better understanding of what it takes to create emotive images.

It is for these many reasons that I have engaged my friend Chris from White Space Films for the second time in the same year to join us this September to make a short film about what it is like to photograph wild Wolves (along with the Brown Bears) in this part of Finland. We start shooting next month and hope to wrap our field shooting toward the end of September with a release of the film before Christmas. Our September workshop this year is long sold out – but we have now opened bookings for our August 2026 Workshop. Details are online HERE. Please get in touch with us if you would like the opportunity to photograph these apex predators in a stunning Autumn setting.

I can hear the question now – What about Winter in Finland? Yes, Winter is possible, and the snow-covered ground and frozen Taiga forest, in combination with the low angle of the sun, can serve as the perfect winter setting and backdrop. This combination alone has fueled my creative imagination and lured me back for repeat Winter visits. However, this time of the year, the bears are hibernating and the wolves are notoriously difficult to see and photograph during the short daylight hours – preferring to visit the hides at night under the cloak of darkness. Over the years, I have tried on several occasions to photograph Wolves in the depths of winter (December / January) in Finland with little to no success. I have seen their tracks and heard their howls on the wind, but that magical image of a wolf softly padding through deep, fresh snow against a frozen forest wall under golden winter light has eluded me to date. Whilst the allure of a soft white canvas, illuminated by winter’s glow, continues to draw me back, it is essential to temper expectations that a winter trip for Wolves can be an exercise in frustration. It is not uncommon to enter the hides at first light, surrounded by recent wolf tracks in deep, fresh snow, only to watch the short golden hours tick past before darkness again envelopes the Boreal forest – without so much as a Raven for company to pass the time.

Autumn, on the other hand, offers not only an explosion of fiery forest colour, but the chance to photograph these predators in the first snows of winter. On several Autumn trips, we have been blessed with snow, and all of the images in the Finland Winter Portfolio HERE of Wolves were made at this time. Autumn is brief this far north in Finland, and the seasonal line is frequently blurred between Autumn and Winter, providing opportunities to photograph in snow when the weather turns toward Winter.

If you are a frequent traveller to this Scandinavian part of the world and looking to expand your portfolio, then you may wish to roll the dice and try in Winter. We will be offering a future Winter trip to Finland to try for Wolves again, but recommend this only to those frequent travellers willing to invest the time and effort, and who understand that failure is a distinct possibility. If it is your first visit (or even second or third) to Finland for Wolves and Bears, then I strongly recommend Autumn as the perfect time to visit for all those reasons listed above. Of course, nothing is guaranteed in Wildlife photography, but you do significantly stack the deck in your favour for both sightings and photographs at this time of the year.

Regardless of when you choose to travel to Finland, the experience of photographing Wolves in the Boreal Taiga forest remains one of the most underrated and rewarding experiences a wildlife photographer can have. There is something very primal about Wolves, and the eerie, haunting echoes of their howls stay with you long after you leave their forest home. This is a workshop I wholeheartedly recommend to anyone wanting to photograph mammals (and specifically carnivores) who doesn’t want to get on a boat. And even those who will happily embark on an ocean-going vessel for their next photograph will find this an experience not to be missed.