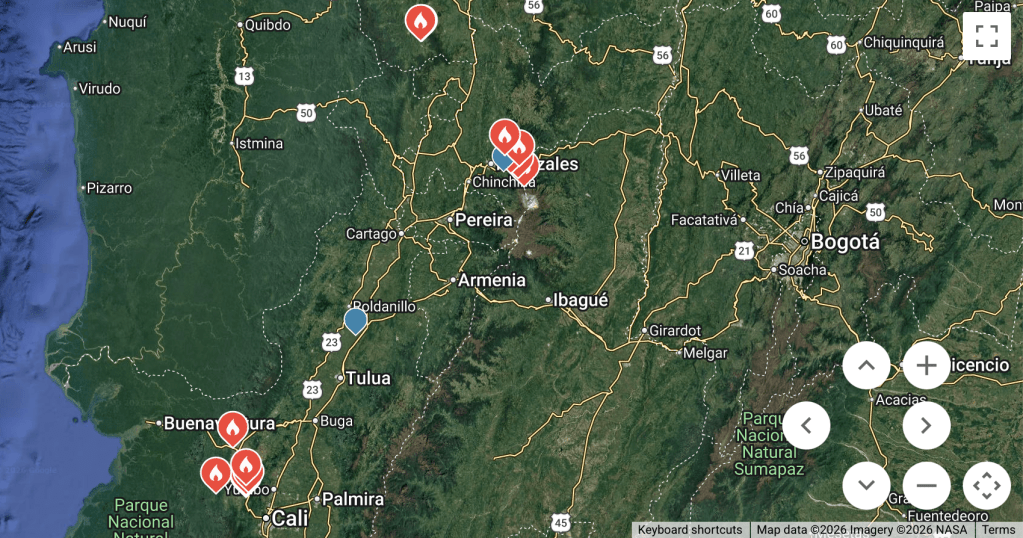

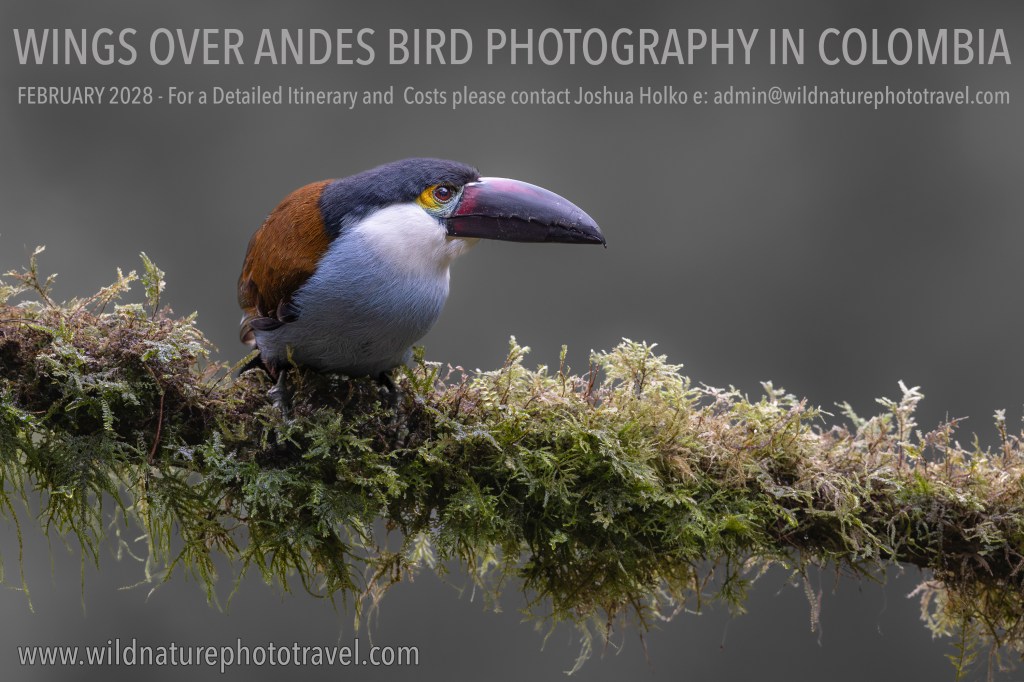

We are well into the first quarter of 2026, and to date I have been in Australia, Mongolia (for Pallas Cat and Snow Leopard), the UAE (United Arab Emirates for the incredible Xposure festival), Colombia (for Birds), and Iceland (for two Arctic Fox trips and a private landscape trip) and in a couple of weeks I will be in Svalbard, north of Norway for both a private Snow Scooter trip and a 10-day boat charter. That’s six countries in just three months, more than 60,000 RAW captures with my two Canon EOS R1s, and a lot of time in airports in transit around the world. And that got me thinking… With all the photography I have already done this year, what do I want to see next from Canon?

Pre-Capture: First and foremost, I want a firmware update to bind pre-capture to a single custom button on the EOSR1. I wrote extensively about this feature request recently HERE, so I won’t belabour the point further. I have subsequently written to Canon Australia and am hopeful we will see this feature via firmware soon. I feel somewhat blessed that we at least have RAW pre-capture, and are not limited to jpeg, as is currently the case with Nikon. As an aside, Sony already allows pre-capture binding (as does the Canon EOS R6 MK3).

RF Extension Tubes: Currently, the RF lens lineup has some gaps that I would very much like to see Canon fill. These include an RF extension tube or a series of tubes. Canon used to make EF extension tubes, and these are extremely useful for closing the close focus distance on subjects in the field. I still own an EF extension tube, but unfortunately, these cannot be adapted to RF glass. There are a number of aftermarket options available, with mixed reviews, but nothing from Canon currently. Extension tubes are most commonly used for Macro work, but they are also a really useful tool for wildlife photographers who want to capture tight headshots of small subjects or small details.

Mega Pixels: 24 is enough for what I do and provides incredible high-ISO performance to boot in the EOS R1. I have no hesitation in shooting the EOS R1 at ISO 12,800 or even ISO 25,600. That said, I would gladly trade more pixels (anything over 24) for even better ISO performance, but I fear we are reaching the limit of physics at this point, and further improvements in ISO performance in the future are likely to be mostly computational. I know others want more pixels for cropping power – I am just not amongst them. If you need more than 24 megapixels, buy an EOS R5 MK2.

Canon Camera Connect App: I would like to see significant improvements in this App that make it more reliable and stable in connection and much faster to use in the field. Currently, connecting to the camera is too slow to be a viable method of camera control for wildlife (most of the time). The app also frustratingly drops its connection on occasion and can be problematic with reconnection. If the application were faster to connect and more reliable, it would turn any smartphone into a fantastic control screen for any Polecam or camera trap system.

Auto Focus: The autofocus in the EOS R1 is the best I have ever used and the camera tracks subjects better than all previous Canon cameras. Its ability to track and stay on the subject’s eye is phenomenal. However, it cannot ‘stay on target’ as well as the EOS 1DX MK2 or MK3 could in heavy snowfall, and has a nasty, annoying habit of grabbing snowflakes in front of the subject. Even tweaking the AF sensitivity settings in the AF menu cannot overcome this issue. This is an issue I have seen repeated on the Nikon Z9 and Sony A1 and A1 MK2 cameras. In general, the AF on these cameras is so ‘tweaked’ and sensitive that falling snow causes continual interference. On my previous 1DX MK3, I could not track the subject’s eye (the camera did not have eye tracking), but I could keep the focus points on the subject, and the camera would successfully ignore falling snow. This could be addressed in firmware with a ‘snow setting’. If we can have a special ‘net’ setting to avoid the net in soccer goals (for photographers shooting from behind the net), we can have a snowfall setting, please, Canon.

Action Priority: Canon has teased us with the initial offering of ‘Action Priority’ for select sports. Further down the line, special focus cases for different wildlife could be a real boon with this technology.

Telephoto Lenses: Over the years, Canon has made both f1.8 and f2.0 EF 200mm lenses. With the RF system, it should be possible (in theory) to make a 200mm lens even faster than f1.8 (or another at f1.8). Such a lens would be the background ‘obliterator’ and an awesome tool in the arsenal of any wildlife photographer whose subject distance can be controlled relatively easily. Penguins, for example, would be the ideal subject for such a lens. Portrait and Wedding photographers would also have strong arguement to employ such a lens. Lenses such as this are highly specialised, but offer creative options not otherwise available. Lenses such as this also tend to be showpieces of what is possible by a manufacturer, but do serve a real functional purpose for creatives.

Super Telephoto Lenses: The much-rumoured 300-600mm RF lens is certainly on my wish list and would complement Canon’s excellent RF 100-300mm F2.8L IS USM lens. I would also love an RF 600mm f4 with a built-in 1.4 or 1.7 teleconverter. The addition of a built-in teleconverter makes a huge difference in the field when you have a subject like a Polar Bear slowly approaching from a distance. Those few seconds saved by flicking in a built-in teleconverter vs having to unscrew the lens and screw in a converter can often mean the difference between getting the shot and missing the best moment. I would also appreciate an 800mm f6.3 DO lens that is small and lightweight for hiking (like Nikon offers), yet still offers incredible reach with a reasonably fast aperture. Such a lens would be fantastic for hard-to-reach targets, such as Snow Leopards or small birds.

Ridiculous Super Telephoto Lenses: Ok, it’s a long shot Hail Mary, but an RF 1200mm f6.3 or f7.1 (Canon used to make an EF 1200mm f5.6) would be wonderful for bragging rights and really small birds. At this focal length, heat haze and air pollution are a real and present danger, so such a lens would be most useful for small birds and other similarly small critters. I can definitely see a use for this lens from the floating hide. The likelihood of such a lens is extremely low, as it would be very expensive to produce and very few would be sold. But Canon would sell at least one!

Tilt Shift Lenses: Canon has made really excellent EF TSE lenses over the years. The 17mm, 24mm, 50mm, and 90mm are all outstanding. I have owned the 17mm, 24mm and 90mm in recent times. All can be adapted to RF mount with the Canon adapter. RF versions have long been rumoured with talk of auto-focus capability. I am not sure I need an AF TSE lens, but I would really like a 20mm TSE in the RF mount. 20mm is my favourite focal length for wide-angle landscape work, and the addition of tilt and shift adds a lot of creative control.

It is still early in 2026 and Canon has not as yet made all its announcements for the year. With luck, we may see some of the above later this year. Let me know what you would like to see from Canon next?

Author: Joshua Holko